Table of Contents

EDITOR'S NOTE

Being a Captain

Khalid Mohidin

Founder and Editor - Cricket Fanatics Magazine

When you think about Leadership in sport, the mind tends to shift instantly to captaincy. The pinnacle title of a figure who represents the decisions, strategy and ideals of how a team plays the game.

In cricket, the captain is held accountable for the success of the team more than in other sports.

Emphasis is put on the way they perform on the field, interact with their teammates, and address the media and the public. It is regarded by many as the most important role in any cricket side.

But what are the common trends when it comes to captaincy? Which characteristics do you need to be a successful skipper?

We explore the role of captaincy in this issue.

As fans, we play a crucial leadership role too. The passion, support and loyalty we show our sports heroes are crucial to their performance. Our observations, or opinions, are integral to building an ambience that motivates and strengthens the mood and performance of any team.

We play an important role in keeping this game alive.

So sit back, grab a snack, a beverage and enjoy our 26th edition of our Monthly Magazine.

Do you want to help us promote South African cricket? Become a Patreon today!

How you can help promote SA Cricket

By Khalid Mohidin

Hey, guys! Welcome to Cricket Fanatics Magazine, the first and only fan-driven Cricket publication in South Africa.

This is a very special announcement that I believe will change the way cricket is supported in South Africa.

I started this venture on 1 July 2019 with a vision to get fans from all walks of life engaged with the game and give them access to the personalities in South African Cricket.

We want to tell the untold stories of South African cricket and we want fans to be heard.

Since we started, we covered the Mzansi Super League, Women’s Super League, Proteas Men and Women International Test, ODI and T20I series, as well as school and club cricket, with the aim of providing entertaining, engaging and educational content.

But haven't stopped there.

We started a Monthly Magazine where we provide multi-media content, including exclusive features, opinion pieces and analysis.

This works hand-in-hand with our YouTube channel where we produce unique cricket shows that allow fans to call in and have their say.

We have the Daily Show, which reveals all the major talking points in South African cricket, the Sunday Podcast Show where we sit back, relax and engage with the live chat, answering all the questions fans have about us and the game.

We have Off-Side Maidens, the first ever All-Women’s Cricket Show on YouTube, which helps empower women in cricket and gives them a place to share their own views on not only women’s cricket but all cricket.

We have a Legends show, where we interview all legends in cricket.

To produce all of this, we’ve invested a lot of money, time and effort to bring this to you for free.

But to keep this going we need your help.

So we have opened a Patreon account.

In the past, the super-rich supported the work of artists as patrons of the art.

Today, we are fortunate that technology has enabled anyone to become a patron of creative work, even if they are not billionaires.

We have therefore launched a campaign for you as a Cricket Fan to become a patron and support us as an independent, bootstrapped publisher.

As a Patron, you also get your voice heard as a Fan.

Plus: You have the opportunity to become more engaged with the content we produce.

Every month we produce at least:

- 60 Website Articles

- 20 Daily Video Shows

- 4 Weekly Podcasts

- Match Previews

- Match Reviews

- Video Interviews

- And more…

So please join our Patreon today initiative today. Even a tiny amount can make a big difference.

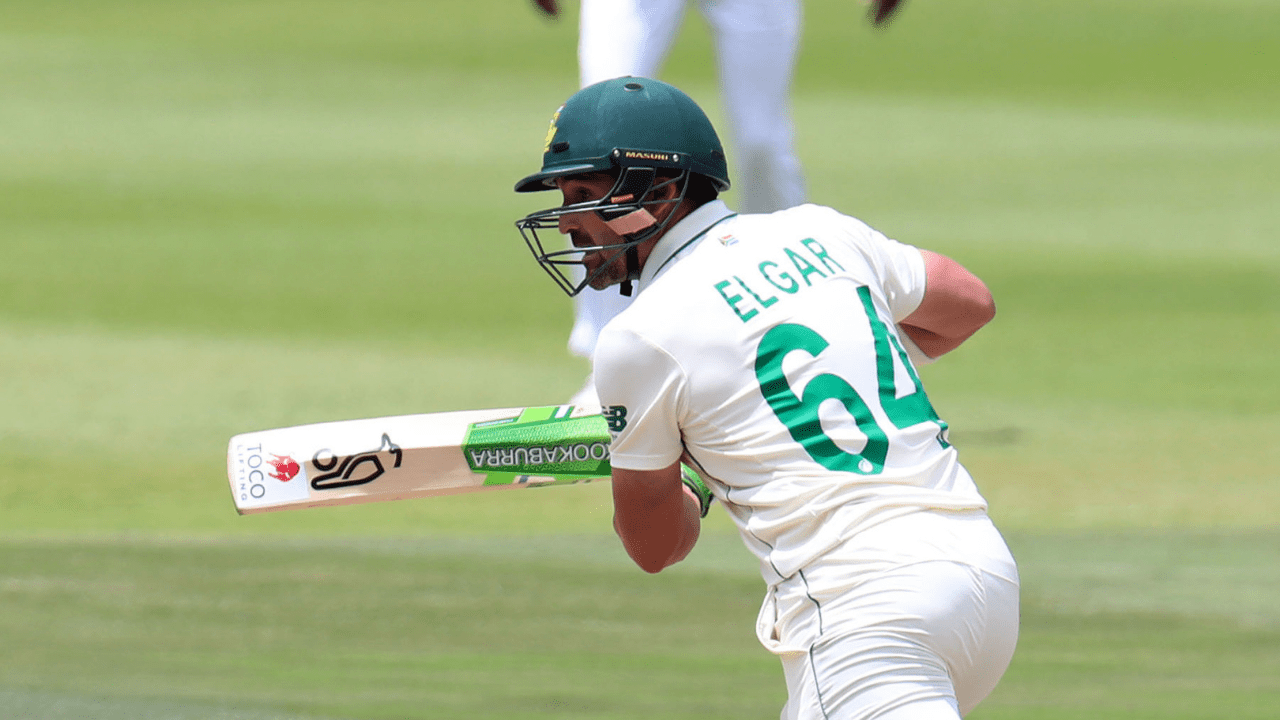

Dean Elgar: In a Spartan Warrior's Cloak

By CS Chiwanza

On the surface, Dean Elgar is the definition of the South African alpha male-type leader. Old school values and tough as nails. But, there is more beneath that.

“International Cricket is a ruthless beast. More times than not, it's not going to go well for you,” says Dean. “So, it is important to me that we create an environment that is safe for everyone in the team,” he says.

Dean sits in front of his prized memorabilia, a few national and domestic trophies neatly arranged in three rows. Perched on the ones at the front are two baggies, his weather-beaten Proteas baggy and his Surrey Championship baggy.

The Surrey baggy is in better condition, as it has not been worn as much as the Proteas baggy. The Surrey baggy is from the 2018 season, the season Dean was part of the team that lifted the Championship title.

'Ornaments in my bowl,' that's how Dean describes them.

"I want to be remembered as the guy who gave his all in service to his country," says Dean Elgar as he leans back in his chair. "I never play for myself, I always want to win for my team and my country. I would like to think that when I am done, I would have left everything out there."

Between the 6th and 4th centuries BC, other Greeks commonly accepted that "one Spartan was worth several men of any other state." Lycurgus, the founder of the iconic army, referred to Sparta as having a "wall of men, instead of bricks."

Dean Elgar personifies that image of Lycurgus’ Spartan warrior. Dean likes to fight in a corner rather than cower in it. He is a leader by what he does. He is always the first one to pick the gauntlet.

Dean believes that if you want to inspire the team to go the extra mile, you have to do more than go the extra mile. Go three or four extra miles. A common sentiment among players he shares, or has shared the dressing room with, is that he leads from the front and stands up for his teammates.

This is a crucial part of the Dean Elgar story. He is firm in his belief that the team is greater than the individual. Nothing frustrates Dean Elgar more than a player who is in it for themselves and themselves alone. He sees it a lot, players who are insecure about their positions within teams not doing enough for the team environment because of an intense inward focus.

“I want guys to realise that this game is so much bigger than you, just focusing on yourself is maybe not the correct way to go about things,” says Dean.

“He is the first guy to front up to a challenge, and that attitude is permeating through other team members. Guys are now fronting up to challenges, wanting to be out there when the going is tough,” says Aiden Markram. “Together with Temba, they are doing great work.”

Dean and Temba have a longstanding relationship built on mutual respect.

“Temba has been a great guy to learn from,” says Dean. “He's the quiet one, I am the loud one. But it kind of balances things out.”

The two captains’ vision for the team, ideas on team culture and environment, dovetail. There is a lot of consultation between the two. Dean consults with Temba on and off-field. Temba is not the only one, Dean’s list of go-to people includes Kagiso Rabada, Keshav Maharaj, Lungi Ngidi and Aiden Markram.

“I don't have all the answers. I wish I had all the answers, but I don’t,” says Dean. “It's never going to hurt you if you go out there and make yourself vulnerable and ask a few questions. They have good cricketing brains. But, it’s not just about what happens on the field.”

Dean doesn’t only check in with the named players. He also asks other guys, even the most junior on the side. Ego is the enemy when it comes to international cricket. Not getting everyone’s input is a poor use of resources. Players always have good ideas. Not only that but knowing that their input is valued helps them feel like they belong. Making it easy for them to take responsibility.

Being asked a simple question, how he thought the pitch would play on his debut, made Kyle Abbott feel at ease in a room full of legends.

This side of Dean, the vulnerable leader who cares that everyone should feel a sense of belonging, is where the Spartan warrior’s cloak falls off. The Spartan warrior image is just the exterior. There is another side of Dean, his best side, that most people don’t get to see.

“Until you know me or until you're my teammate and you see me operating behind the scenes, you will always see a one-dimensional image,” says Dean. “Behind closed doors, I am very different. People don’t know the kind of work we have done behind the scenes with the team in the past few months.”

“I don't think many people will see the care he has for the players, the environment and the badge,” says Aiden Markram. “That care factor is really good from Dean.”

JP Duminy, who was Dean’s Proteas teammate from 2012 to 2017, always found the Proteas captain to be someone one could count on, on and off the pitch.

“When it was a tough situation, he was there for you,” says JP Duminy.

When the Proteas were leaving for the New Zealand tour, Dean was one of the last people to arrive at OR Tambo airport. He went around greeting every team member individually and had a quiet word with them. He asked about the ones that had not yet arrived and sought them out when they came through.

One part of that is Dean Elgar just being Dean Elgar. He was raised to have manners and be a decent person, a decent member of a collective. The team had not seen each other in a while.

The second part is Dean Elgar the captain.

“We were about to go into the unknown, going into waters most of our guys were extremely unfamiliar with,” says Dean. “We have a pretty inexperienced and young players group, it was important for me to make them realise that we were walking the same walk. Little actions like me doing that, making sure that everyone is on the same page help. They also communicate that there is no hierarchy, in a way.”

Dean Elgar toddled his way into cricket. Three-year-old Dean generally followed his older brother, Dale, everywhere. When Dale went to the backyard, Dean was right behind him. When Dale went next door, Dean was right behind him. Martin was the name of the boy next door. Whether at the Elgars’ home or next door, Dale and Martin spent a lot of time playing cricket.

Of course, Dean didn’t follow to watch them play, he wanted to take part too. But, he was more of a nuisance than he was a play partner or competition. All he did was get in the way. He was too small to do much with either bat or ball. Despite being sprightly, his arms were not yet built to compete. The older boys often gave him a little leeway, pretended he was not out when he was out and things like that.

Dean was barely five. Even at that point, it was clear that Dean had a thing for sports. He was reasonably coordinated. Part of the reason could be the genetic lottery. Dean’s father was a keen and able football player, and his mother was a proficient dancer.

“If you put a ball at my feet I could kick it and if you put a racket in my hand, I could hit the ball,” says Dean.

With those qualities and an ability to run, Dean was a natural at most sports during his school years. Rugby was not on the list. Dean was just too short. His height, or lack of it, also meant that bowling was also out of the equation. But, he was good at what he stuck with, particularly squash. He could have pursued the sport professionally but didn’t because the rewards do not match the effort one puts in.

All cricketers start out as pace-bowling all-rounders, and Dean was no different. Dean converted to spin as a teenager after his coach told him that he would not be booming bowling pace.

“When he told me, I took a lot of offence because I thought I had a bit of pace,” says Dean.

Dean switched to spin. But, he would rather have a half-fit Keshav Maharaj, one arm in a sling, bowling ahead of him.

Anyway, as soon as he found his way around a bat, Dean flipped the game on its head. There was excitement and fun in hitting a six and getting out for the older boys. The bigger the six and out, the better. Dean got stuck in and batted to stay in. It pissed the older boys off.

“There used to be lots of arguments because Dean never wanted to stop batting,” says Dean’s father. “But, that said, Dale and Martin were always accommodating towards Dean, they always allowed Dean to have another go if he was out.”

A study found that some boxing managers pitted their fighters with boxers of slightly lesser ability to help them generate psychological momentum. Wins breed confidence, confidence breeds success and success breeds success. Research shows that ‘players update their beliefs about their abilities after experiencing an initial success.’ They evaluate their skills differently compared to those who have not experienced success.

A combination of lucky breaks, leniency and success based on his limited skill helped Dean’s confidence.

As Dean grew older and more competitive, the leniency subsided. Whether it was cricket, squash or football, Dale turned the screws. Being six and a half years older, it was effortless for Dale to do so. But, Dean behaved like a small army, outnumbered and outflanked, but somehow surviving and occasionally prospering. Sometimes coming very close to complete victory.

The way he took beatings from Dale, as he termed them, is not so different to the way he takes body blows on the pitch. He takes one, winces, and forgets about it to face the next delivery.

It's uncanny, for some reason, Dean seemingly gets hit on the body more than most batters. It is as if he bats on a custom-made surface that he rolls out when it's his turn at the crease.

Dean gets more body blows at home, especially at Centurion and at the Wanderers, where the pitches can get spicy. It could be a case of recency bias, but Dean won't soon forget the hits he took in the Test against India in 2022. That is the match that he mentions first when you ask him the time when he has taken the most body blows.

He is not the only one.

“Dean took a few hits in that match against Indies at the Wanderers,” says Aiden Markram. “There was this one ball, I think it was Bumrah who was bowling. It pitched on a length, spat up, and hit Dean on the grill. It was a tough blow, but Dean sort of shrugged it off and continued batting. He was unbeaten at the end of our innings. That’s Dean.”

That Spartan indifference to pain and fear is what many people associate with Dean. But, whatever the reason for the high number of body blows, it's definitely not by design.

"I don't like it," Dean laughs. "If I could get out of the way more, I would. But then, if taking hits helps me do a job for the team, then so be it."

Graeme Smith was 12 years old when he decided to embark on the path to becoming the future Proteas captain. If the world was surprised when he ascended to the position at 22, Graeme was not. 10 years earlier, a preteen Smith had proclaimed his destiny with a note that read, ‘I will be captain for my country.’ He stuck the note under a fridge magnet.

At 12, Dean had a different dream. He wanted to play cricket at Goodyear Park. That was his mountain. Dean wanted to play against the best Free State had to offer at Goodyear Park, and he wanted to compete against the country’s best at Goodyear Park.

Years later, it would take a monumental effort from Farhaan Behardien and Heino Kuhn to get Dean to move from Goodyear Park to Centurion. Dean, Farhaan Behardien and Heino Kuhn have a long history. The trio attended the national academy together. Dean was the younger of the three, fresh out of school. Dean’s move to the Titans would have been a reunion.

Behardien and Kuhn even got creative in their attempts to lure Dean to Pretoria. One evening after the Eagles had played against the Titans in Pretoria, Dean was sitting in the Titans’ change room when they snuck up behind him and made him wear a Titans jersey. Two years after the jersey incident, Dean left the Eagles after eight years of playing for the side.

“There was a lot of manipulation to get me to the Titans,” says Dean. “At the Titans, I learned what it's about to play for something bigger than you.”

But, Behardien and Kuhn’s efforts were not just because they wanted their good friend to play on the same team as they were. The Titans had just lost two openers. Blake Snijman had retired, and Ghoulam Bodi had crossed the Jukskei to join the Lions.

“We really thought Dean would add value, and it looks like we were right,” says Behardien.

Behardien was also right about Dean captaining the Proteas. It is a conversation the two had when they roomed together at the national academy. But Dean’s focus then was on Goodyear Park.

“I was just focused on scoring runs for the Eagles that I'm never really looked too far,” says Dean. “The problem is if you look too far you actually lose your vision of where you want to go.”

To realise his Goodyear Park dream, Dean recruited everyone within touching distance to help him with training.

“During school holidays, Dean and Dale would spend hours in the nets at school with the bowling machine,” says Dean’s father. “They would be out there, just batting for hours on end.”

Dean had what Ellen Winner, author of Gifted Children, calls a rage to master. They are intrinsically motivated to be good at their chosen field. On Sundays, while his friends were at church, Dean was in the nets with his father manning the bowling machine. Dean’s father did not only avail himself on weekends if needed, but he also did so during the week.

“My saving grace was that my dad never said no to me when I wanted to train,” says Dean. “If I said to him, ‘Let's go to the nets at three o'clock.’ He never said no. He would work hard and skip taking lunch, to make sure that we could go to the nets at three o'clock. When I was around 14 or 15, I would go and join the club side and train there after my session with my dad. It was a never-ending, non-stop innings.”

Dean’s father was at all of Dean’s matches. He made time to be there. One of his favourite innings was when Dean was in Standard 7. St. Dominics was playing against a school from Kimberley. Dean scored an unbeaten 130, his school chasing 200 to win.

“I think it finally dawned on me that he could make a career out of cricket when he was selected to captain the SA Under-19 team that went to India to play in the Afro Asian tournament in 2004. Then I was convinced beyond doubt after he captained the SA Under-19 World Cup team to Sri Lanka in 2006,” Dean’s father says.

Like all proud fathers, Dean’s father has watched every one of Dean’s international matches, live or on TV. When the Proteas were in New Zealand, his schedule changed. Each time Dean bats, he sees the young boy who wanted to be the best batter.

According to Winner, children with rage to master their field show an intense and obsessive interest and an ability to focus sharply. ‘They experience states of flow when learning about their domain and lose sense of the outside world. The lucky combination of obsessive interest in a domain, along with an ability to learn easily in that domain, leads to high achievement,’ Winner writes.

Marathon net sessions in the company of either Dale or their father would never have been enough to elevate Dean into the kind of cricketer he became. At 14, Dean was already competing against adults at club cricket level. Mr Klopper, a St Dominics teacher, took his game to the next level.

“Mr Klopper and his wife opened their home to me,” says Dean.

Dean saw Mr Klopper at school, he was his teacher and cricket coach. Then Dean saw Mr Klopper at his home because Dean was friends with Mr Klopper’s younger son. They also saw each other at club cricket where Dean played for the same team as Mr Klopper’s older son. It was as if teacher and student were joined at the hip.

With the Kloppers, Dean had a second family. Mr and Mrs Klopper’s sons became more than friends to Dean. They became brothers.

Mr Klopper saw something in Dean. He also saw dedication and courage. Dean faced batters with the same attitude he embodied facing an opponent on a squash court. He did not give them an inch. While Dale and Dean’s father are responsible for Dean falling in love with the sport and investing a lot of time into Dean’s practice, it was Mr Klopper who made Dean into the player he is, technically.

No one knows Dean’s batting more than Mr Klopper. Because of Mr Klopper, Dean excelled at cricket.

“We still chat,” says Dean. “We talk almost before every match.”

It was not just cricket that he pursued relentlessly.

Dean was a multi-talented youth, though not to the scale that AB De Villiers was during his time at Affies. De Villiers is recognised as the youngster who was basically the Swiss Army knife of sports despite his modest protests. De Villiers always demurely claims that he was ‘decent at golf and useful at rugby and tennis.’

Dean was a decent athlete and handy on the soccer field. The outside was my classroom, he contends. But with growing demands on his time when he started playing club cricket as a teen, soccer and athletes fell away, and he focused most of his time on squash and cricket.

A lot of things make sense in retrospect. Their significance only comes when you look at things afterwards and replay them like a short film. Looking back on how everything unfolded, you suddenly develop a clarity that you did not have when it took place.

Dean's second season with the Eagles defined the player he would grow to become. In perfect order, his first three seasons followed this order; high highs, low lows and then rebuilding.

His second season was a trainwreck of a season. He suffered a bout of second season syndrome. The bowlers had figured him out, and he averaged in the mid to low 20s across formats. In his first season, Dean played 10 games for the Eagles. His second season average was a fraction of his debut season average.

Dean scored 97 on his debut. He had to sit out the next match because the incumbent, Jacques Rudolph, had returned from Proteas duty. Instead of drifting to the B-side, Dean begged the coach to allow him to travel with the team to their next match.

This was his summit. He wanted nothing more than to be a part of the team, whether he was playing or not. If he didn’t make the playing XI, he would rather be in the dressing-room with the selected players.

“I just wanted to be in the squad. That is all I wanted,” says Dean.

The coach told him to expect nothing besides 12-th man duties, fetching drinks, and carrying towels. As the 12-th man, he was also expected to do a lot of lugging. The senior players expected him to grab and carry their bags from the carousel at the airports.

During Dean’s first few seasons, the Eagles operated as the agoge. In ancient Sparta, the agoge was the city-state’s educational and training program that prepared young boys to be Spartan citizens and soldiers. The agoge was crucial in developing upright citizens who valued harmony and cooperation in their society.

As a junior player, Dean’s responsibility included a lot of lugging. At away games, Dean was expected to lug senior players’ bags to and from the carousel. Guys would literally get the boarding tickets, leave the bags, and you'd have to put the bags on the belt at the airport. The changeroom was also his responsibility, Dean had to keep it clean, no water bottles were to be found lying around.

“The guys I played with were pretty ruthless about responsibility and everyone taking ownership of our duties,” says Dean. “They would bite your head off if you did not take care of your responsibilities.”

Senior players felt that their responsibility lay in keeping the team on track on the field and helping junior team members develop as cricketers. During Dean’s sophomore season, they held his hand as he struggled to put runs on the board. Not once did Dean feel judged for performing poorly. The team backed him.

Before his debut, Nicky Boje, the Eagles captain, had told him to either fit in or bugger off. It was not so much a threat but a warning that if he did not assimilate into the team culture, he would find the going hard because there was no way the team would adapt itself to suit him. The collective overruled the individual.

“Dean takes great pride in serving the team,” says Aiden Markram.

Times have changed, it’s no longer the ‘old world’ where junior players went through a modern-day version of the agoge’s trial by ordeal to prove that they fit in. But to Dean, the virtues and values he learned from that period are still applicable. A team member has to take pride in serving the team environment.

“You are either giving or taking away from the environment,” says Dean. “I learned how to serve my environment in those early years. How we learn to do that is different, not everyone should go through what I went through, but the lessons learnt are still relevant.”

Of course, it was not a one-way relationship. The older players did everything from minor things like serving him food and drinks after a match to giving him time and advice in the nets and changeroom.

After his 97 on debut, Dean scored an unbeaten 225 in the next match he played. At 19, he laid claim to a spot in the team. However, his second season was the opposite of his debut season.

Up until that point, Dean had never really struggled for runs. He had no idea what that was like. After that season, it was easy for him to look into the mirror and see failure staring back at him. An average in the lower 20s as a top-order batter is a failure.

Dean was afraid of failure. He was afraid of being dismissed for a low score. Through the second season, Dean played with that fear heavy on his mind, as he got to learn in the offseason during conversations he had with the psychologist provided by the Eagles. Besides his sessions with the sports psychologist, Dean stayed away from cricket for most of the offseason.

He did not handle his bats. He had them safely tucked away and did everything else besides a net session. He played squash, did fitness drills and explored life outside of cricket.

In his first two seasons, Dean had approached cricket the same way he had approached backyard cricket as a youngster, he batted to stay in. But, when he came back for the third season, he had a different mindset and a different goal to strive for. He no longer batted to stay in, he batted to contribute to the team’s total. It remains one of the most valuable lessons of his career.

Dean emerged from the offseason wiser and tougher, a different and better player. He still did not like losing, but he now had a different relationship with failure.

"I've failed so many times in the last decade and a half, that I have learnt to be comfortable with it. I am secure knowing that it doesn't define you as a cricketer and it doesn't define you as a person," says Dean.

People tend to forget the details. Everything that happened shrinks to a footnote, and one thing stands out, the runs and wins columns. Cricketers, on the other hand, have this uncanny ability to recall even the tiniest details about a match. Ten years after a match, they remember the weather, the state of the pitch, the field setting and a few other details.

The Proteas had been reeling as someone hit by a surprise punch would. With two early wickets, thanks to Peter Siddle and Josh Hazelwood, the visitors were 45 for two in the first 20 overs. South Africa was at the risk of reproducing the same performance as in the first innings. Besides Quinton De Kock and Temba Bavuma, who scored brave 50s, everyone else had fallen cheaply.

But Dean was not going to trudge away with his tail between his legs. He was in the mood for a fight and just needed someone to hang around with him. It happened to be an in-form JP Duminy.

“The thing about Dean is, it doesn't matter what's happening around him, who's chirping him or the situation of the game, he always has this quiet confidence about him,” says JP. “He also has the ability to portray resilience through tough periods. I fed off that energy.”

In between overs, the two left-handers came together and touched gloves. Their conversations were the obvious fare, what to look out for from different bowlers and talking through the conditions - what works, what doesn't work. Then there was the occasional word of encouragement just before each returned to their crease.

The duo batted contrasting innings as they weaved a 250-run partnership that wrestled control away from the Australians. JP Duminy faced fewer balls than Dean and scored more runs. JP faced 225 balls for his 144. Dean, on the hand, faced 316 deliveries for his 127. An insecure batter would have tried to up his strike rate to match JP Duminy’s. Not Dean.

During Australia's second innings, Kagiso Rabada made the ball do everything humanly possible. Everyone almost expected to see him perform a yo-yo trick with it too. Rabada had everything that day; pace, bounce, seam, conventional swing, reverse swing, searing yorkers, and the ability to target cracks in the pitch.

Dean has carried his bat three times, as many as Desmond Haynes. He remembers each occasion well. It is a record that Dean is proud to hold, one he hopes to improve on. He would love to carry his bat a record four times.

But, the times he carried his bat are personal records. They offer proof to the world of the sort of player he is - was, if looking back in the future. Unlike opinion, records are indisputable. But those matches will always be remembered as Dean Elgar’s innings.

The match against Australia at the WACA was different. Dean contributed in a big way, and so did others. JP Duminy, Vernon Philander, Kagiso Rabada, Temba Bavuma, Quinton de Kock. It was a Proteas effort. Much like the match against India at the Wanderers.

The Spartans’ real secret in making them a formidable army was not their indifference to pain and suffering. That was only a small part of it. Their biggest weapon was their superior organisation. Spartan troops were drilled relentlessly until they could execute tactics with perfection.

“Dean puts in a lot of hard work into preparation before a tour or a series,” says Aiden Markram.

Before the Proteas' tour to the Caribbean, the team and coaching staff were huddled around a fire at a hotel in Irene. It was a cold night. The veterans knew a talk was coming, and the new guys were about to learn something new. A lot of the Proteas’ things revolve around a fire. It holds an important place in the team's activities.

That night, Dean gave a talk about 'climbing Everest.' The Proteas were seventh on the World Test Championship table. The only acceptable route from here would be up. Hopefully, the team would make it all the way to first place. Dean had been there when he was part of Graeme Smith’s side, and he liked the feeling of being the best in the world.

They needed to find ways and means to play the game in a way that could get them there. They could not leave the controllables to chance. One of the things agreed on was to be more assertive. The other thing they talked about during their sequestration was the need to take responsibility. Responsibility for the team is not a one-man duty, it’s a shared thing among teammates.

Dean made no bones about it. The Proteas were not going to wake up at the top of the rankings the next day. Victory in the West Indies was not going to guarantee that either. It was also not going to take a year. It would take longer. It takes progression by inches. Progression by inches requires discipline and repeating a set of behaviours that take the team forward.

Dean did not have to give this type of talk when he captained the SA Under-19 team. All he had to do was to be tactically aware. Even then, he was heavily reliant on the coaches. He did not have to do any man-management.

The next time Dean had a chat as intense as the one at Irene was in New Zealand. The Proteas had just lost the first Test.

Mark Boucher did not think it was the right time to talk with the players. Everyone was still raw from the humiliation on the field, emotions were running high. The Proteas had been skittled for 95 and 111 in the first and second innings. The whole team looked lost at sea and dropped four catches as New Zealand piled on 482. The Proteas lost that Test by an innings and 276 runs.

“I think this is when coach and captain relationship comes into into play,” says Dean.

Boucher trusted Dean’s judgement.

Across the corridor, the despondent Proteas players heard the New Zealand players celebrate and declare that the Black Caps were on course to break a long-standing record. New Zealand has never won a Test series against the Proteas.

“I don’t mind losing, it’s how you lose that matters,” says Dean. “Against New Zealand, we did not play at the expected standard. We lacked the intensity that a winner comes into the match with.”

Sometimes, someone like Mitchell Johnson, one of the fiercest bowlers Dean ever played against, would raze a batting lineup. That can happen. It can also happen that someone like Brian Lara would play an incredible innings. Or it can simply be that the other team played at a higher level. That is not what happened in Christchurch.

"We were undercooked and played below par," says Dean.

Dean did not rip into his teammates. He spoke about the team, the Proteas, and then he spoke about the badge: what representing South Africa entails. He spoke about how everyone, including himself, had not played at the expected level.

“I actually reflected back onto the chat that we had in Irene,” says Dean.

Dean reminded them that blowouts happen, they are a part of the sport. The defeat against New Zealand is the stuff nightmares are made of. Dean urged his teammates to treat it like a nightmare, forget about it and move on.

“I also told them, ‘It's about your pride. It's about the badge that you have on your chest, that’s what you're playing for. It's about guys that have played in these positions before. Those guys have been legends and custodians of our cricket, of the Proteas brand. We are today’s custodians of the badge, and I feel we've let everyone down, we have let the brand down and we have let ourselves down immensely by the way we performed in that Test,’” says Dean.

Dean did not give another speech after that. Not even on the morning of the second Test. He did not think it was necessary. He trusted that his teammates had taken on board what he had said after the defeat. The Proteas kept their record against New Zealand by winning the second Test by 198 runs.

Between 26 December 2021 and 01 March 2022, Dean Elgar and his team defended two long-standing records. Against India, their opponents in December and January, the Proteas had also fallen behind after the first Test. Though they did not lose as badly as they did against New Zealand, the assumption was that India was finally going to win a series in South Africa.

Three - nil, some had predicted.

The next talk Dean will have with the team will be just before the next tour. In the offseason, in between golf and other pursuits, Dean has been taking stock of the past season. He doesn’t want the previous successes to lull the team into a comfort zone. He identified areas that need improvement.

The team also needs to find a way to deal with difficult times when they arise. Winning goes a long way in making the team a cohesive unit, but that can fall away once the team starts losing.

Bad days are coming. No team, no matter how talented and well oiled, is invincible. At some point, the team will lose a series. It is crucial to prepare for that. How they lose, and how they respond to loss will determine whether they can be a top team or not.

Fans love match-winners. The only thing they love as much as match-winners is a winning team.

“The greatest feeling and sensation that you can have in playing cricket is to win. And ultimately I will do anything to get over that line,” says Dean Elgar. “I always thought of myself as a team person that would do anything for the team, I'll run through walls for the team.

"And I have always thought my personal aspirations or my personal pride is always going to be second place to the team because the team is the greatest, and the team is greater than you. I have always been willing to put the team first, knowing that if we do the right things we get the results.”

Managing Mavericks

By Aditya Mehta

Captaincy is 90 percent luck and 10 percent skill. But don’t try it without that 10 percent. - Richie Benaud

Cricket experts typically discuss captaincy in the context of tactics, people management, and a captain’s win-loss ratio.

Captaincy continues to be a fascinating topic of discussion in cricket because of the degree to which a captain’s tactical acumen can influence the outcome of the game. South Africa has had its share of astute captains in Hansie Cronje, Graeme Smith, Faf du Plessis, and now, Temba Bavuma.

The art of captaincy has been extensively covered in books and on television by former captains. This piece aims to focus on the key to successfully captaining ‘mavericks’ in a cricket team.

A maverick, for the sake of this discussion, refers to a player of extraordinary natural ability. This is an important discussion because every cricket team in the world has produced mavericks, but they have not always been successfully managed.

Kevin Pietersen is an example of a maverick whose tremendously successful career with the England cricket team ended prematurely owing to challenges, allegedly, posed by his “divisive” personality.

The jury is divided on Pietersen’s influence on the English dressing room. While some, such as former England captain, Michael Vaughan, argued that Pietersen was a difficult personality who could be managed, others, such as former England captain, Andrew Strauss, said it became increasingly challenging to manage Pietersen in the team.

Irrespective of the contrasting views on Pietersen’s personality, it is undeniable that he was a matchwinner for England and someone who opposition teams feared more than any other batter in their lineup at the time.

The late Shane Warne, Pietersen’s captain at Hampshire, made an interesting observation about bringing the best out of Pietersen.

“I captained KP at Hampshire, it didn’t take very long to work out that he likes KP. It was a matter of how you could get the best out of KP because you knew how good he was, and I was one of his biggest supporters when he wasn’t in the England side.

"I said, ‘How could England not pick this guy? This guy is a matchwinner. This is what they need.’ I did that in 2005 before the Ashes. I wanted him in my side, I knew he was good. It was about the leaders getting the best out of him.

"You have to make him feel important. How England, eventually, treated him – they said, ‘Mate, you just go out there and make runs, we’re going to worry about what’s going on.’

"That was wrong. Kevin Pietersen had to be made to feel important, that was to get the best out of him. Things like – ‘KP, what do you think we need to do today?’ I used to walk out and say, ‘KP, what do you reckon, mate? Who should be 12th man?’

"I had already made the decision, but I wanted to make him feel important that he is a part of the leadership group. He’s so important to the team, and I’m making him feel important. That’s how you get the best out of those guys. And you don’t let them get away with one inch. If they step out of line, you’re the one that nails them. Absolutely straight away.

"If you let them get away with a little bit, then he’ll take a mile. You got to nail him straight away. These are the team rules. But you got to make him feel important. And that’s where England went wrong at the end.”

South Africa and world cricket will always produce mavericks. By all accounts, South African youngsters, Dewald Brevis and Tristan Stubbs are equipped with the skills to be among the best in the world.

At present, they are still finding their feet on the global stage, but once they do gain international experience, it is imperative that their captains manage their individual temperaments to get the best out of them for South Africa.

New! Business Corner

Cricket Fanatics Magazine has the visibility, infrastructure, expertise and toolset to promote your brand, business, product or service.

Strong Captains win Matches

By Alasdair Fraser

They say good luck is when opportunity and preparation meet but in cricketing terms it’s more likely that a strong, inspirational leader with a certain trait of characteristics both on and off the field to engineer the luck required to consistently win Test matches.

The West Indies had Clive Lloyd; the Aussies had Allan Border, Steve Waugh, and Ricky Ponting; South Africa had Hansie Cronje and Graeme Smith. Those teams in the annals of cricketing history were dominant and have gone down as real juggernauts that seldom tasted defeat.

Even the late Shane Warne possessed all the attributes of a successful leader who should have gone on to greater heights with the Baggy Greens. His captaincy skills shone through when the highly unfancied Rajasthan Royals won the inaugural Indian Premier League in 2008.

In a South African context, we have seen the likes of Clive Rice’s Mean Machine Transvaal in the 1980s, Cronje’s 1990s Proteas and later under Graeme Smith’s assured leadership – albeit it took time for the latter to grow into his role and benefited from the unbelievable talented crop of players he had at his disposal later in his 11-year tenure as Proteas captain.

Rice’s leadership skills stemmed from his ultra-competitiveness to win at all costs – even when the chips were down his ability to inspire and lead from the front with his masterful bowling and never-say-die attitude rubbed off on his powerful unit. We’ve seen a similar style of captaincy from England’s Ben Stokes.

Cricket is that unique sport in which players perform individually within a team dynamic. The ability to get the most out of those individuals, while guiding them, shone through Rice’s aggressive approach.

His experience of captaining Nottinghamshire in the unforgiving County Cricket circuit ultimately honed that hard-nosed approach he was famous for. Rice had the uncanny ability to beat his opponents and get one over at the coin toss.

All that, though, cannot be achieved without the services of world-class players who can turn a match on its head in a matter of overs. As with the Windies of the 70s and 80s, and the Aussies who took over that baton for nearly two decades.

There have been instances where a team full of superstars have not performed to the best of their abilities such as India, who at times have struggled with strong leadership, but that changed dramatically after Gary Kirsten – a strong believer in having good leadership structures in place – took over the Indian coaching reigns.

It is no coincidence that under Cronje and Smith’s watch, the Proteas enjoyed highly successful winning streaks in the longer format over a sustained period, while the former was in charge of a well-drilled ODI outfit that was brutal in its approach and one run away from potentially being crowned world champions in 1999.

Cronje’s path was helped with the Grey Bloem connection that he shared with Kepler Wessels. It was Cronje who was named vice-captain under Wessels when the promising Free Stater was the youngest player in the squad.

He took over the captaincy role after the 1994 tour of England at the age of 24, which no one had a problem with at the time, and although there were a few bumpy rides in the earlier stages, Cronje conquered every single Test nation in a series except Australia.

Beating a star-studded Pakistan outfit away was nothing short of exceptional but the 2000 Test series win over in India was Cronje’s crowning achievement – not even the mighty Australians at the time were able to achieve that mammoth feat.

Forget about the match-fixing scandal that came straight after that impressive triumph, Cronje’s leadership skills were never doubted and often admired as forward-thinking. Cronje was 29 when the saga broke, and it would have been interesting to see what his record ended up being had he captained the Proteas to 100 Tests.

Smith’s path was similar to Cronje’s in many ways, however, he was not afforded the same power as Cronje and was forced to live in the long shadow of the match-fixing saga. It would have been interesting had Cronje not tragically perished in a plane crash to see how it may have played on Smith’s mind.

Smith announced his arrival as captain with a truckload of runs – the perfect statement and answer to his initial critics, who deemed the 22-year-old as too young to captain a Test side. But Smith will be the first to acknowledge that he learned on the job for his first three years as skipper.

That learning went way into 2006 and the steep curve flattened after Sri Lanka taught the Proteas a major cricketing lesson. By then, Smith as already building a side with fresh blood in Hashim Amla, Dale Steyn, Morne Morkel, AB de Villiers, Ashwell Prince, JP Duminy and to a lesser extent Paul Harris, whose role in how the Proteas pace attack strategically bowled as a unit should never be downplayed.

Although not half the cricketing brain that Bob Woolmer was, Mickey Arthur allowed Smith the same freedom that Woolmer afforded Cronje to show true leadership and give 100% responsibility to own the captaincy role and manage his troops. Yes, there was a clique, but all great Test teams need that changeroom nuance to be able to ‘click’.

From 2007 to Smith’s retirement, the Proteas dominated Test cricket and became No 1 in the world across all formats in early-2009 and came agonisingly close to emulating Cronje’s cricketing feats in India on two occasions. The 2012 tour to England was Smith’s second Everest before he tasted a second series win away to Australia later that year.

The current Test set-up sees Dean Elgar in charge and his leadership skillset is like Smith’s. Opening the batting and leading from the front with a gritty, hard-nosed approach has served his charges well and complements the Protea Fire.

Since the Windies Test series last year, Elgar has managed to get the best out of his team. The Proteas possess one of the more powerful bowling lineups in world cricket. Elgar has enough guile and determination to milk the cream from his bowlers.

Against India and New Zealand, we’ve witnessed come-from-behind displays that are the hallmark of a side that never gives up. For once, against England, Elgar held all the cards in the first Test, and he will need to summon his ability to get his men up for the fight that awaits his team in the deciding third Test.

Win a series against England, and Australia later this year, and Elgar can rightfully earn the plaudits his strong Test captaincy deserves.

Advertisement

Ezra Poole's Online Wicketkeeping Academy

Learn how to Master The Craft of Wicketkeeping Without Having to Hire a Full-Time Personal Coach.

Sibonelo Makhanya's transition to captaincy

By Abhai Sawkar

Over the course of the last couple of seasons, many promising youngsters have confidently stepped up to the plate and announced themselves. South African domestic cricket has only become more and more competitive when it comes to players striving to rise through the ranks.

Enter Sibonelo Makhanya. You might recognize his name from the Proteas Under-19 squad from eight years ago. Not long after the World Cup glory, he’d make his professional debut for his home state of KwaZulu-Natal.

Even though he would make it to the franchise level for the Dolphins, it wasn’t always the easiest of times. He remained in and around the squad and even had a chance to play for the South Africa Emerging team on a few occasions, but he wasn’t necessarily a staple feature in the Dolphins side to a great extent.

After a successful run in the 2019 Mzansi Super League for the Paarl Rocks, he’d soon arrive at a crossroads on what to do next.

Makhanya decided to relocate to Pretoria in 2020. This was a decision made following plenty of deliberation, and he sought a change in scenery and a new challenge that would regularly keep him engaged. He has embraced his new team and has done well to adjust.

“I started my career at KZN for the Dolphins. Before leaving, there were many people who tried to have a conversation with me about moving and how it would potentially benefit my career, and at the time I didn’t quite understand it.

"But around the time I left, I had reached a point where I felt like I was becoming a bit too stagnant and too much in my comfort zone. It seemed like my career wasn’t progressing in the direction I originally planned. I realized that it’s time to make a move, and I took a chance.

"Fortunately, it’s worked out quite well for me so far. One thing that’s evident is the new environment I stepped into. It’s quite challenging there, and you’re always on your toes.”

Since his early cricketing days, Makhanya was proficient with both and ball. However, upon arrival at the professional scene, he had little choice but to make do with the role he was assigned. And that role was not static; he was frequently shunted to various positions in the batting order, and his bowling was sporadically used.

He was aware that he had to carve out his niche as a cricketer before pushing for greater honors, and he finally found the balance when he became more fixated on his batting. And the change in plans helped transform his approach into a more free-wheeling style in the middle order.

“Initially I started off as an allrounder, probably to my detriment because in most cases, I never really felt so sure of what my role was in the side. In some games, I played as a bowling allrounder and in other games, as a batting allrounder. So I couldn’t really focus on specifics, and I wasn’t quite sure where to channel the focus.

"My bowling slowly took a back seat and it was quite obvious that my batting will either keep me in the XI or regularly get me into the XI. It was simply a shift of focus from trying to be able to do everything to concentrating on one thing and giving it my all.”

After making telling progress, Makhanya was finally put in charge of the Titans side during the most recent Momentum One Day Cup. It was a watershed moment for the 26-year-old, and he was raring to go. Understandably, it was another steep learning curve, as this was the first time he had risen to captaincy in the domestic scene.

Then again, it was all about adjustment. Considering the Titans side has a well-rounded amalgamation of youth and experience, establishing a friendly rapport with everyone can be a little tricky but a testament of Makhanya’s modus operandi as a cricketer is to always be organized and ready to solve problems.

“Captaining a top-tier domestic side is definitely a challenge. The easy part is having high-quality players around you, but it’s also tough when you’ve got a lot of big personalities that you have to manage.

"In saying that, those players make your job easier given their level of experience and knowledge they bring to the table. It’s a catch-22, but I’d happily have it this way since it forces me to grow quicker.

"When you stand up in the dressing room and deliver the final word, there's a certain level of accountability and you do a lot of things with conviction. That’s helped me develop my game, and you definitely feel that the things you say carry more weight compared to the times when you’re just a player.”

Humility has been central to Makhanya’s growth and development as a cricketer. A prominent motivational figure for him was the incumbent Proteas skipper at the time, who would leave behind a strong, lasting impression in Tests. And for Makhanya, the objective for the leader is to ensure that the team smoothly gels together, and that everyone is able to always perform at their highest intensity.

“I’ve had the pleasure to play under a lot of great captains, and from all of them, I got the luxury of picking the things I liked. I also got to understand what kind of captain I’d be if I was given the chance.

"By no means am I saying I am a finished product - in fact, it’s still the beginning of my journey and I’m learning every day. Faf du Plessis was one that I’ve had the pleasure to work under and experience how he went about his business. I think his biggest key was how he was able to relate to all his players, from the inexperienced to the more seasoned players, and get the best out of them.”

As far as preparation was concerned, Makhanya kept things pretty simple. Taking charge of the Titans side was a new responsibility on his plate, and the main priority was to make sure that the mutual interests of the team came before anything else. Fortunately, he soon became comfortable in his new role and there has been no looking back.

“I didn’t change anything about the way that I was. I’ve always looked to lead in the way I do certain things. Captaincy was just a title that allowed me to do what I do with a much larger audience and more influence. I always try to selflessly serve others and put others before myself. And this wasn’t something I was seeking or trying to achieve. It was put on to me as a challenge, and it worked out nicely.”

Makhanya got his first taste of captaincy earlier this year, and the Titans came tantalizingly close to winning the One Day Cup. They may have lost the final to the Lions, but the solid run up to that point was very much a catalyst.

He was establishing himself as the trusted middle-order finisher, with 3 half-centuries in 8 games, at a brilliant strike rate of 116. As much as he was excited to be able to cash in on the opportunities presented, he eagerly expressed a desire to add to the trophy cabinet.

“The 2021-2022 domestic season was a rather successful one. As a team, I felt we were great, considering we made the finals across all three formats. That was an awesome achievement. But there’s always room for improvement, and it would’ve been nice to win all three trophies. That’s what we’ll strive for going forward.

"We were in a rebuilding phase and to have a season like we did, it speaks volumes about the work done behind the scenes. Individually, I was happy with my consistency but I’d love to improve in converting my good starts into big scores and winning more games for the Titans.”

Off the field, Makhanya has always looked up to his family for motivation, especially his father. He is very appreciative of all of what he has been through as a child, as it has been instrumental in shaping his personality as well as his outlook.

Even at club level, he was constantly kept on his toes and emerged stronger from each experience. Ultimately, his thought process is very straightforward: in the areas that are in your control, be true to who you are and give it your all.

“I’ve learned a lot from my dad and the way that he raised me, especially the way he handles the household and teaches us with unconditional love and care. Another inspirational figure is Kugen Subrayen - Prenelan Subrayen’s father - and he was one of the biggest influences in my life when it comes to cricket and leadership skills.

"He forced me to learn about the game at a young age as well as speak up in front of people even if it felt uncomfortable. When I was playing club cricket, he was the president of the club side I played for. I think it’s all these little things from then on that have held me in good stead coming to today.

"Finally, I get inspiration from sports superstars from around the world. We’re so fortunate that there are so many documentaries out there from which we can learn about how they lead from the front just by how they conduct themselves. The most important thing is to be yourself, because that way it’s sustainable and you won’t burn out.”

Traits of a Captain

By Lubabalo Skhosana

"Any captain can only do his best for the team and for cricket. When you are winning, you are a hero. Lose, and the backslappers fade away," a statement by the late Richie Benaud that speaks to the challenges of being captain.

Captaincy is one of the toughest jobs in cricket and yet seldom spoken about. Well, captaincy always tends to be spoken about when the team is not doing well.

It is broad and complex not only because of the definition of the role but also its demands in general. Complex as it may be, captaincy plays an integral part in the functioning of a cricket team and the success of that very same team.

Selecting or choosing a captain is, to some extent, synonymous with the saying: "There are many ways to skin a cat."

There are also many ways to choose or select a captain. Different ratiocination is used for the selection of different captains. It all depends on the person selecting the captain. However, some traits are important in a captain.

As already stated, being captain is one of the hardest jobs in cricket because it carries a lot of weight and comes with a lot of heavy responsibilities.

An opener could easily get a golden duck only for the number 3 to come in and smash a double hundred.

A bowler could bowl a wide ball only to get a wicket with the extra ball.

A mistake made by the captain, however, could very well lose the match for the team seemingly instantly.

Bowling your part-timer at the wrong time and holding your best bowler back until it is too late are examples of decisions that could easily go against you and cost you the match.

Depending on the level of cricket you are playing, you might not live such mistakes down.

Captains, much like coaches, will often have their performances highlighted when the results are not in their favour, but everyone forgets they even exist when results are positive.

As a captain, one needs to have a sense of resilience and a thick skin. Good captains are generally the ones who have thick skins and are resilient because the role of captaincy comes with many challenges.

A captain who can weather any storm regardless of its ferocity will always be priceless. A good captain is also a good communicator.

Those who lack communication skills will never make a good captain because captaincy requires someone who's direct and clear. Someone who says what they mean and means what they say.

Perhaps a guy like Graeme Smith or Ricky Ponting also comes to mind. Both are known to be very bold and clear about what they want to say.

There is a lot of communication involved. The captain is the one person that needs to communicate with everyone. From coaches, teammates, and umpires, to ground staff and even the media.

So, if your captain lacks communication skills, something is bound to go wrong and there is bound to be a communication breakdown along the way.

There are a lot of other traits that one must possess to be a good captain and one of those is good leadership skills.

Leadership in general is a bit like captaincy in terms of being complex. This is why some people tend to think that everyone who is a good leader is automatically a good captain which is not necessarily the case.

One can be a good leader and not be a good captain, but one cannot be a good captain if they are not a good leader.

A good captain can display good leadership skills and can lead from the front. And when necessary, from the back. "Good leaders are good followers."

With most traits there comes another important part of captaincy – The ability to read games and having a good understanding of the game of cricket in general.

The roles of a captain on the field are built in a way that requires someone who can read the game and someone who understands the game. Field placings, bowling changes, a decision at the toss etc.

All of these things require one to have a good understanding of the game of cricket and to be able to read games because most of these decisions are influenced by the trajectory of the game and the direction it may be taking at that time.

Maybe the toss is that one thing a captain never has full control over.

Captaincy remains an essential role in cricket. Perhaps even more important than that of a coach on match day. A captain can lose or win you matches as they are the primary decision maker during a match.

We have also seen how a captain can become a champion for change in a positive way. Virat Kohli changed the fitness standards of the Indian team and Eoin Morgan changed how the English team played white-ball cricket. Both of these gentlemen are captains who drove the change for their teams and nations as captains.

Captaincy may be spoken about selectively but it remains integral to a team's success so appointing the right person as captain will always be key.

Q&A: Bryce Parsons

Tell us how you started your career in cricket. What were some highlights in your formative years?

Cricket for me has always been my sport of choice, since as long as I can remember it’s always been cricket. My earliest memories were playing U8 club cricket. Most of that is due to my parents’ support and willingness to always throw balls at me and do whatever it took to get me to be the best I could, I couldn’t thank them enough for everything they did for me.

Some of my highlights throughout the years was being named SA U19 captain for the 2020 World Cup. It was always a dream to represent my country.

And then looking back during my school days scoring 3

double hundreds at school was definitely moments that made me realise that I can pursue the game for a living and gave me that belief that I was good enough.

You made your debut for Gauteng in the 2019/2020 CSA Provincial T20 Cup. How did you feel at that moment?

It was a proud moment for me, as any young cricketer dreams of making your professional debut, it was slightly unexpected as I was pretty young still in school but a proud moment for me and the beginning of my journey.

Once the squad gets announced you don’t have much time to prepare you just have to back all the preparations you have done beforehand, more just trying to get in the best frame of mind and not let the occasion get the better of you.

In 2021, you were part of the SA Emerging Men’s Squad for the 6-match tour to Namibia. What did this mean for you and your career?

It's another stepping stone to hopefully play for the Proteas one day, a great honour to be recognised as one of the top youngsters in the country and representing your country in games is always a privilege.

Hopefully, I can kick on from here and repay everyone for backing me through the pipeline to date.

You were named captain of the SA Squad for 2020 U19 cricket world cup. How did you keep your team motivated and disciplined? What were your goals for the team at the time? You were also the leading run-scorer. How did you keep yourself motivated and disciplined?

It was a huge honour for all of us so it wasn’t that hard to get the boys up and motivated we were playing for our country in what was the biggest games of our careers at the time so there wasn’t much I needed to do to get the guys motivated, I think the biggest thing I had to do was speak to the guys and try not let the occasion get to us stay calm under pressure.

It was a home World Cup so we went into the competition to win it, we lost to the eventual winners which was disappointing as we felt we could have gone further with the squad we had.

I think I had to lead by example, I tried to take the game by the scruff of the neck and put the best foot forward to give the team the best possible chance.

If I was doing well it would feed confidence in the whole group so I prided myself on my performances so other players could see it was possible to do well at that level.

What are your aspirations with regards to captaincy?

I would love to captain the Proteas one day, it’s always been a goal of mine. But I have to keep learning from the guys here at the Dolphins I think we have some really good leaders here that I can learn from so just keep picking their brains and hopefully I get those opportunities in the future.

What is your philosophy as a skipper?

I would like to think I’m a pretty aggressive captain not giving the opposition time to settle in being unpredictable , always try and keep the culture of the squad strong because I think that’s really important if everyone is close it makes you want to fight for one another and I think that brings out the best in players.

Also in batting, what have you learnt in red-ball cricket, particularly as a top order batter?

I took a lot of learnings from last year, obviously opening the batting in your first season of franchise cricket is never going to be easy and you have to figure things out. Luckily I had Sarel Erwee to pick his brain and speak to him about the challenges you face at the top of the order and the 2 big pieces of information I’ve got from him was try play late and straight , and watch the ball closely, it sounds really simple but just those 2 things gets you looking to score in the right areas to be a solid opening batter.

What have you learnt from the captains you worked under?

It's very easy to see that the captains we’ve had at the Dolphins have years of experience they have been around a while and have a natural instinct about the game , learning from Subrayen last year he has a never give up attitude he will always be the hardest worker in training and is very competitive on the field and that’s what any player could ask for from a captain , he sets the tone and will never take a backwards step which is great for other players to see him leading from the front.

Describe a day in the life of an all-rounder. What is the best/worst part?

I have always been a batting all-rounder despite an up-and-down season with the bat last year but been working hard and my batting feels in a good space at the moment.

Pretty normal days for all-rounders, got to do everything start the day off with gym work and then head into the nets, get your bowling loads in for the day and then do your batting work, so days are a bit longer but I guess it’s just part of the game when you do both disciplines. But the best part of the day has got to be going in for a bat during a net session.

How do you deal with dry spells?

I have always found it hard went through it a bit last season and found myself doubting my ability but I just think you have to stay consistent with your preparation even in dry spells I think I went through a stage of trying too hard. But I think you just have to keep believing in yourself and keep believing that runs are around the corner.

Who or what keeps you motivated and grounded especially when you are feeling pressure?

Well I have no reason not to be grounded haven’t achieved much in the game at all so it’s just keep working hard to one day look back and be happy with what you achieved, I’m always motivated as I’m not where I want to be I want to make the step up into international cricket one day and I need to improve my performance to do that so there is no lack of motivation.

Who are your favourite cricketers?

I’ve always looked up to someone like Graeme Smith being a leader at a young age and I’ve always kind of tried to emulate a similar career, coming from the same school and his career speaks for itself.

Whose wickets would you dream of taking?

There are so many big names that I’d love to get out but probably Babar Azam at the moment potential the best all-format play going around at the moment so he’s got to be up there.

Who is your fantasy opening batting pair?

Quinton de Kock and Rohit Sharma

What advice would you give other youngsters who also aspire to start a career in cricket?

Follow your dreams, there are always going to be people along the way who tell you that you aren’t good enough or don’t think it’s the right path for you but if you believe in yourself and work hard there

is always a chance, never give up on a dream.

What do you do to relax?

Try to play as much golf as possible to switch off from cricket

Do you have a nickname among your teammates?

There’s been plenty of nicknames thrown around at me over the years but I think everyone has just stuck with BP can’t say the others in a magazine.

If you could travel anywhere in the world, where would you go and why?

Would love to go to the Caribbean, it looks amazing and think it would be a good time.

What are your top 3 songs on your playlist?

St Tropez: J Cole

21C Delta: Jack Harlow

Rollin: Ryan Trey

Manchester United or Liverpool?

Liverpool, my parents supported them so growing up I was always a Liverpool fan.

What is your favourite series/movie/documentary?

Ozark is my favourite series, and a movie I enjoyed is Red Notice.

What types of food do you enjoy the most?

Pizza

Daily Show | Let's talk about it

Video Playlist

The Podcast Live Show:

Exclusive Interviews

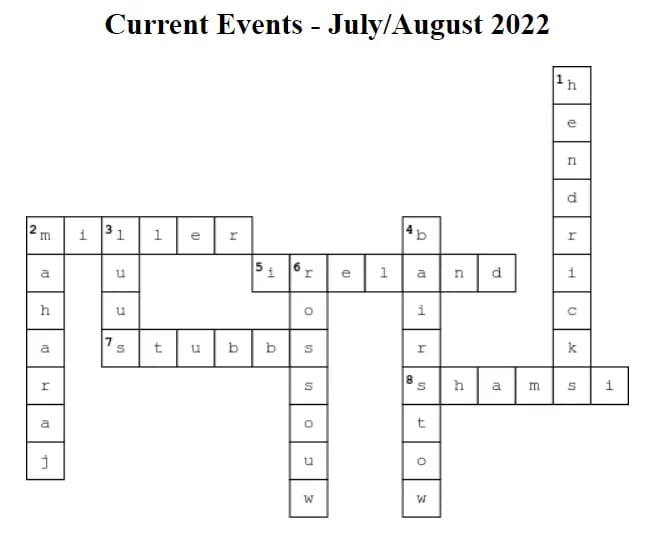

Crossword Puzzle

Current Events - August 2022

ISSUE 25: Crossword Answers

Magazine info

Editorial Director

Khalid Mohidin

IT and Technical Director

Faizel Mohidin

Contributors

Alasdair Fraser

Abhai Sawkar

Aditya Mehta

CS Chiwanza

Jessica October

Janine October

Khalid Mohidin

Ravi Reddy

Graphics

Khalid Mohidin (Cover and Graphics)

Images

BackpagePix

Supplied

Twitter

Facebook

Video Binge List:

On Lockdown Series

The Podcast Show

Legends with Ravi

Daily Show