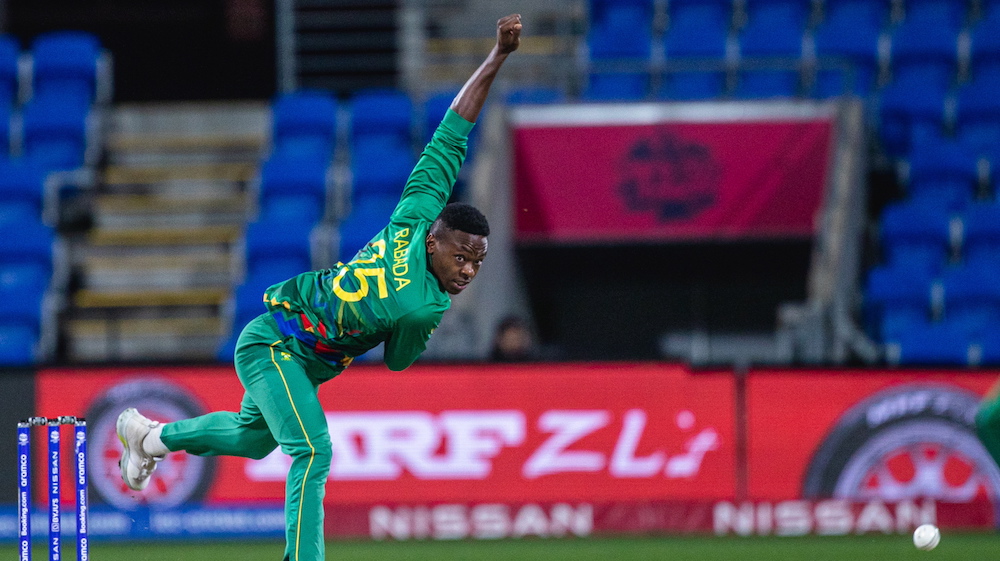

When he goes for a net session, Kagiso Rabada carries with him two balls. A new ball and an old ball. He also gets there with a set plan. A plan informed by what he is working on. His plan is not affected by who the batter is, Rabada does not pay attention to that. His only focus is his bowling.

Kagiso Rabada is a technician and understands that the only way he can do that is if he keeps things as simple as possible. “I give myself every opportunity to get better during practice,” says Rabada.

During pregame training, Rabada is consistent in what he works on; he mixes up his lengths. He bowls some length balls, a few short balls, a sprinkling of yorkers, some cutters and other slower ball deliveries. With each delivery, the focus is on landing the ball in the right area, not what the batter is doing.

That is the formula that has helped him to become of the premier bowlers of his generation.

The universe of sports writers and fans love it when athletes have a rich history, a backstory, that helps make sense of their greatness. Shane Warne bowled from a run-up of a few steps because he broke both legs as a kid and spent a couple of months wheeling himself on a trolley – his shoulders got so strong he didn’t need the energy created by a run-up. Lungi Ngidi’s father was a maintenance man at the affluent primary school where Ngidi eventually learned how to play cricket.

Makhaya Ntini was born to a poor Mdantsane-based family, cricket changed his life so much Cricket South Africa created an award after him – the Makhaya Ntini Power of Cricket Award. The award is given to a player whose life has completely changed because of cricket. The inaugural recipient of the award was Ottniel Baartman. When he was a teenager, if Baartman bowled well, his family could afford dinner – they were that poor.

Kagiso Rabada doesn’t have such a backstory. He had an idyllic upbringing. Conventional by middle-class standards. His parents, Mpho and Florence Rabada, are accomplished professionals – a doctor and an asset management specialist. Rabada’s family was intact and enjoyed middle-class comforts. There is no apparent trauma.

Mpho and Florence did not have it easy during apartheid and were grateful to provide Kagiso with everything they lacked growing up. But, they made sure that he understood how fortunate he was. They shared with him stories of their past, and every year around Christmas, they took him to the poor townships to hand out hampers to the needy.

In its own way, the unremarkable nature of Rabada’s childhood makes the success that followed even more remarkable. How did this kid who grew up under pleasant circumstances become one of the most phenomenal bowlers of his generation?

When he was 14, Rabada bowled what his father would later recall as the fastest delivery he had seen until that point.

St. Stithians were struggling to take the last wicket in a timed match. Rabada put his hand up. With his first delivery of the over, Rabada sent the stumps cartwheeling.

There is something gladiatorial about Kagiso Rabada. He is relentless. During his years at St. Stithians, Rabada’s cricket master Wim Jansen started a cricket walkway alongside the path around the first team oval. Whenever a player took a five-wicket haul for the school, a tree was planted and a nameplate attached to it. Rabada made it his mission to get at least one tree planted in his honour. Unfortunately, he always fell short. He took more four-fors than he cares to remember.

After his five-wicket haul for South Africa U19 at the U19 World, Rabada got in touch with Jansen to ask if the school could now honour him with a tree and a nameplate. Jansen and Ian Rickelton saw no harm in bending the rules for one of their own. Rabada has kept his former masters busy by constantly updating the plaque beneath the tree with his achievements on the global stage.

When he arrived at St. Stithians Rabada was a hotshot fullback that went head-first into tackles, scuffles and scrums. Almost immediately, Rabada went through what researchers call a sampling period. A sampling period is when athletes take part in more than one discipline, in the manner one would do if they are trying to find the perfect fit for themselves.

Between the ages of 11 and 14, Rabada took part in rugby, soccer, tennis and track and field athletics.

Kagiso Rabada’s multi-sport childhood is the subject of a few reams that speak of late specialization. It is the antithesis of the Tiger Woods version that resonates with so many in the cricket universe who believe in early specialization and private coaching. Rabada followed the Roger Federer path, if I may call it that.

There is no single perfect way to develop talent, but, Rabada’s athleticism is a result of his holistic sporting ability as a youngster.

Rabada pared down his sporting commitments in his mid-teens, just as Federer did when he decided to exclusively focus on tennis. Once he decided to focus on cricket as his primary sport, Rabada developed an attachment to the cricket ball.

“He always had a cricket ball with him,” says Enoch Nkwe. Nkwe was Rabada’s coach at Gauteng U19 when the bowler was 16.

Those days, Rabada’s parents knew that they would always find him in the gym whenever they went to pick him up from Gauteng U19 training sessions. Kagiso Rabada was relentless.

“He still does the things he did as a teenager,” says Nkwe. “He never shied away from asking questions. He also did a lot of research on his own – how to improve his bowling, and nutrition – he studied best practices from different sports codes and tried to see where they fitted in with him. At 16, he bowled on the same level as senior provincial players. One thing he did was nail the fundamentals.”

Rabada is still relentless in his focus on nailing the fundamentals.

Photos: BackpagePix