Quinton de Kock’s ability and talent is too great to be hampered by what number he bats for the Proteas, writes Khalid Mohidin.

One of the major talking points after the 1st Test in Pakistan was the poor batting display by Quinton de Kock.

The Proteas skipper scored 15 and 2 in his two innings against Pakistan, with fans understandably upset with the result due to the manner he lost his wickets and at the time the fall of wickets took place.

Other than the captaincy, another variable has been argued to be the reason for his failure – his batting position.

I’m going to stick my neck out and say – my observation is that this isn’t the reason for his dip in form. But to back this up, firstly, I will have to look at Quinton’s career so far and present you with the stats.

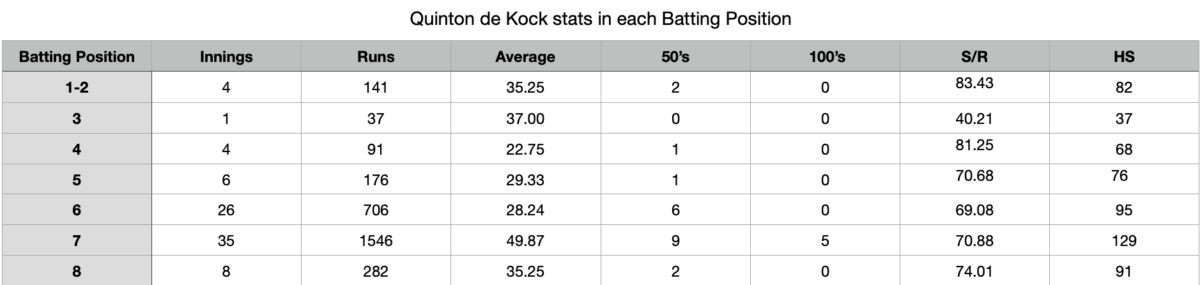

In 50 matches played by De Kock, the 28-year-old has 84 innings under his belt.

In that time he has batted in all the positions in the batting order from opener down to No 8.

Here is a table of his stats for each position:

Now at first glance, it is easy to say: “Quinton de Kock’s highest average is batting at 7 so he must bat there. De Kock scored all of his centuries at No 7, therefore he must bat at there.”

To counter that, he’s biggest ever dip in form came between 14 July 2017 and 1 March 2018, he went through a dry spell of 15 innings without a half-century, batting at 6 and 7. Currently, it’s only been 5 innings without a half-century batting at 5, dating back to the 76 he scored against England at the Wanderers on 24 January 2020.

But I want to delve deeper, and look at the reasons why batting positions are not so important when it comes to De Kock.

One of the hardest jobs in Test cricket is facing the new ball. On a pace-friendly strip, coming out to the middle and facing a side’s two quickest bowlers, can be a daunting task. Even worse, facing bowleres who get movement with the new ball.

Batting high up the order can be perceived as being more difficult, especially in South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and England.

As an opener (1-2), you face the ball when it’s new, as well as when the ball deteriorates slightly and starts to swing.

If you are a middle-order (3-5) – depending on whether there’s a high opening stand or batting collapse – you face the ball mostly when it swings or when it’s old. Only massive batting collapses would see you face the new ball.

If you bat in the lower-order (6-7) – you tend to bat with the tail. The most ideal situation, you come in when your top order put at least 250 on the board, and you take the side deep into the 400’s. But the flip scenario, you come in after a batting collapse and try and save the side – no coach would see that as a gameplan.

If you are in the subcontinent, you are generally facing the spinners when the pitch has deteriorated and when patience is required to persevere. Generally, your middle-order being comfortable against spin becomes vital to success in the subcontinent.

Although we have seen spinners open with the new ball and hamper openers on dusty tracks, generally the older the ball gets, the more dangerous spin becomes on turning wickets.

You may be thinking: “Khalid, where the hell are you going with this?”

Well bear with me, I’m going to try and revisit De Kock’s innings’ where we have seen the best of him, free flowing and in fine form.

Let’s start with his maiden century in 2016 – 129 not out against England in Centurion. The Proteas batted first. Hashim Amla and Stephen Cook put 232 runs on the board, setting an amazing platform for the Proteas. But after the loss of Amla, the Proteas could only work their way to 273-5 after 77.1 overs.

This was when De Kock came to the crease. The second new ball was taken in the 80th over, and despite losing Bavuma after a 62-run stand, De Kock stuck around till the end to marshal the tail and score a much-needed 129 not out. He showed great skill to see off the second new-ball against some of the best bowlers the game has ever seen. The Proteas ended up scoring 475. They also won the consolation match, with England having already sealed the series 2-1.

This gives a great argument as to why he should bat at No 7, right?

Let’s move on.

De Kock’s 104 against Australia in 2016. Australia came out to bat on a green track in overcast conditions in Hobart. Vernon Philander’s swing troubled Australia and their innings was over before tea. The Proteas bowled the hosts out for 85. When they came in to bat it was primetime for seamers to knock over batsmen cheaply.

They suffered a major collapse, 132-5 in 42.4 overs when De Kock came to the crease. With the ball reverse-swinging, De Kock, despite coming in at 7, had to face Australia’s pace attack after a batting collapse. On this particular day, whether he had come in at 4, 5 or 6, it would not have mattered. Senior players in JP Duminy (1) at No 4 and Faf du Plessis (7) at No 5 were best suited for the situation at that particular time in the match. But they went out quickly.

De Kock scored a match-deciding hundred in tough circumstances that fully tested his ability with the bat.

In both scenarios he walked out to the middle at a time that should have been more suited for a No 4 or 5 batsman. He conducted business for his side, showing his versatility and importance to the side as a batsman.

For his third century – 101 against Sri Lanka at Newlands. The Proteas were struggling at 169-5 after 60.5 overs when De Kock came to the crease. It was a bouncy Newlands track and the Proteas’ batters struggled to handle Saranga Lakmal and Lahiru Kumara who did the bulk of the damage.

But yet again, De Kock came to the crease in a match situation that would have been ideal for a quality No 4 or 5 batsman, and put on a marvellous attacking batting display. The swing didn’t bother him and he put the Proteas in a good position.

In an even better example, his fourth Test century – 129 against Pakistan at the Wanderers. The Proteas, in their second innings, found themselves 29 for two after 8.4 overs, 45-4 after 14.5 overs and 93-5 after 28.3 overs. Once again, De Kock came to the crease needing to play in a match situation that shouldn’t be an issue for a quality No 3 or No 4 batsman.

He went on to score 129 off 138 balls against a clearly lethal Pakistan seam attack, on a pitch conducive to pace and scored at a strike rate of 93.48 to help the Proteas post 303.

His 111 in India, emphasises my point even further – De Kock, on the dustiest subcontinent wicket that the hosts could prepare, came to the crease after the Proteas were bamboozled by Ravichandran Ashwin and Ravindra Jadeja. The team were 178-5 after 57.3 overs, following a resilient 75 from Faf du Plessis in a 115-run stand with Elgar.

Elgar ran out of middle-order partners and De Kock came to the crease in the toughest spin-friendly conditions and managed to score 111 off 164 balls. While the Proteas ultimately suffered a heavy defeat, De Kock proved again, that when faced with conditions and confident bowlers that you would expect your top No 3 or No 4 batsman to handle, he would come out on top.

Now I have only covered his centuries, and only on one occasion did he come in as a “conventional No 7” when his side had significant runs on the board. The rest of the times, he was essentially coming into the match at times when the middle order had collapsed.

When I look at his half-centuries coming in at No 7 – out of the 9 half-centuries he scored – on 6 occasions he came to the middle when the top 5 collapsed. Once out of the 6 occasions, the top order managed to score 201, all the other times it was significantly lower.

Coming in at 6, he scored 6 half-centuries. The first time he scored a half-century at 6, he walked out to the middle with the total at 246-4. The second time he walked to the middle the score was 157-4. The four remaining times the top order failed to reach 100.

Some say No 5 is too high for De Kock. Yet, in his first-ever Test match, he opened the batting. He scored two half-centuries against New Zealand in Centurion, not bad for “someone who can’t bat any higher than No 6”. (Remember, he also opened the batting for the Lions at Franchise level.)

The point here is, that very seldom when De Kock came out to the middle was he needed to bat as a conventional “No 7” or 6 – coming out when there are runs on the board and propelling the team to a massive total.

Fun fact about Adam Gilchrist, batting at 7, out of the 12 centuries at that position, only 4 times did Australia’s top order score below 200.

De Kock has always needed to right the ship to keep his side’s chances alive. Or play in conditions or with the pressure of scoring that a No 3, No 4 or No 5 batsman should be more suited to handle.

A great argument to say why he should bat at No 7, is that De Kock is coming to the wicket when he knows he’s the last recognised batsman standing, so it pushes him to perform – but this is a mental capability that we can’t prove.

What you can prove, is that in the majority of the games that he’s scored runs in, he has had to face World-Class bowlers with energy levels up and conditions that suit them. Coming in at a time when a No 3, No 4 or No 5 failed to flourish facing challenges they should be able to handle. He has conquered those challenges – whether it be in England, South Africa, India or New Zealand.

If the Proteas built their middle-order around him, it could be the answer to solving our batting collapses. But is this the right choice seeing that No 7 is his best position?

De Kock has proven to be talented enough to bat in multiple pressure situations.

If he drops the gloves, he can bat anywhere in the top 4.

With the gloves, there is no reason why he should not be able to perform at No 5. He is talented enough to bat anywhere in the top 5 as a batsman alone.

His bad run could be a mental issue. Maybe being captain and the wicketkeeper at the same time is weighing too heavily on him, or maybe it’s the bubble life taking its toll on his mental state.

One thing’s for sure. It’s definitely not his ability or talent that’s the cause for De Kock’s dip in form.

Disclaimer: Cricket Fanatics Magazine encourages freedom of speech and the expression of diverse views from fans. The views of this article published on cricketfanaticsmag.com are therefore the writer’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Cricket Fanatics Magazine team.

WE ARE 100% BOOTSTRAPPED. BECOME A PATRON AND JOIN US ON THIS JOURNEY.